By: Mwiine Andrew Kaggwa

Imagine a weary traveler, Uganda’s soul emerging from the shadows of war and tyranny, seeking a path to peace. In 1995, a new covenant was forged through the Constitution, its Preamble a solemn vow to unite a fractured nation singing in unison “in pursuit of unity, peace, equality, and justice.” Article 7, declaring no state religion, which became its sacred cornerstone, welcomes all, including Christians praying for mercy in the lines of Micah 6:8, which calls to act justly with love and mercy, Muslims striving for fairness under Qur’an 4:135 to uphold justice, and others bound by faith. This was no mere law, but it was a call to transform hearts, to weave a tapestry of devotion where every soul could worship freely. For a people scarred yet hopeful, the Constitution’s Preamble and Article 7 promised a legacy of righteousness to what became A Nation’s Sacred Covenant. This article asks whether this covenant unleashes a sacred transformation, stirring Uganda’s faithful to unite in justice and love.

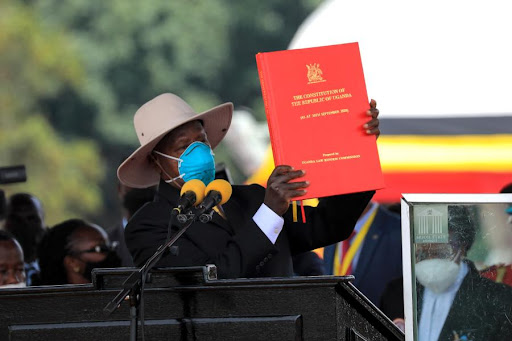

Consider this from the perspective of a secular code in a devout land. Envision a storyteller whose voice is rich with memory, sharing Uganda’s dawn in 1995. Then the Constitution’s Preamble, declaring “We the people… united by a common destiny,” rose from turmoil’s embers to bind a wounded nation. Its foundations are heralded by Article 7, screaming “Uganda shall not adopt a state religion”, Article 21 asserting that “All persons are equal before the law”, and Article 29 also affirming that “Every person shall have the right to freedom of religion” all of which shaped a secular bulwark for Christians, Muslims, and others—celebrated as a pinnacle of African constitutionalism, which promised impartial governance. Yet, in a land where Psalm 33:12 praises the blessed and Qur’an 16:90 urges justice and compassion, this legal frame feels remote. Corruption endures, executive dominance, which is marked by the 2005 term limit removal challenges Article 1’s sovereignty, and moral clashes test Article 7’s pluralism. To Uganda’s devout, this code seems a distant rule, not a spark for their fervent spirit. Might this Preamble’s vision kindle a sacred shift, uniting the faithful in a righteous legacy?

Now we ask ourselves, is the Constitution a Covenant for Transformation? Does it mirror the Biblical Reframe?

Let’s talk about Uganda’s 1995 Constitution, and this time, not just as a stack of laws, but as something bigger, something sacred. Imagine it as a promise, like a heartfelt vow to pull Uganda together after years of struggle. It is not about dry rules, but rather it is about changing how we live, how we treat each other. Take Article 28, which propounds the “Right to a fair hearing” calling for justice, straight out of Deuteronomy 10:19, where God says to love and be fair to all. Or Article 31 protecting families, echoing Qur’an 2:177’s push for compassion and righteousness. These aren’t just legal lines in the alternative; they are a nudge to act with kindness, to see every person, whether Christian, Muslim, or otherwise, as part of Uganda’s family. The Constitution urges us to live out faith, to turn belief into action, whether in Kampala’s bustling streets or Arua’s quiet villages. It’s a call to fairness and love, which is rooted in something holy. So, what if we saw it as a covenant, not just law? Could it push us to transform, to build a Uganda where faith fuels not only a shared but also a righteous future?

| Aspect | 1995 Constitution Provision | Religious Teaching | Alignment | Divergence/Critique |

| Human Dignity | Article 20: “Fundamental rights… inherent” | Isaiah 1:17: Seek justice, defend the oppressed | Upholds God-given dignity | Enforcement gaps (e.g. abuses) defy justice |

| Social Justice | Article 32: Affirmative action for marginalized | Qur’an 3:104: Enjoin what is right | Promotes fairness for all | Poverty persists, challenging compassion |

| Fair Hearings | Article 28: Right to fair hearing | Isaiah 1:17: Seek justice | Supports impartial dispute resolution | Court delays undermine swift justice |

The above is a Snapshot of Faith in Action; the table is a quick map showing how Uganda’s 1995 Constitution lines up with faith. It is not just legal jargon, but it is proof that the Constitution can push us to live better. Article 20, saying rights are “inherent,” vibrates with Isaiah 1:17’s call to defend the oppressed, reflecting pure God-given dignity. Article 32 lifting marginalized groups through affirmative action, matches Qur’an 3:104’s push for doing right by everyone. And Article 28’s fair hearings! That is justice in action that comes straight from faith’s heart. The table lays it out as these laws aren’t just rules, but they are a nudge to act with compassion, whether you are Christian, Muslim, or aligned elsewhere. But it also shows where we stumble, like corruption or delays, holding us back. It is a wake-up call that these provisions can spark a real change in how we treat each other by building a Uganda rooted in faith.

As we dream to align ourselves to this, this legacy will meet challenges, tensions and gaps. So, what I am saying is that the Constitution is this sacred spark, but then let us be honest, it is not all smooth sailing. Uganda’s 1995 Constitution has big dreams, but reality sometimes trips it up. Article 44 provides that no one can mess with core rights, like freedom from torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, and Article 126 pushes for a fair judiciary. This sounds great, doesn’t it? It is like Proverbs 29:2, which says, “When the righteous thrive, the people rejoice.” Or Qur’an 7:56, allaying that “Do not spread corruption on earth”. But corruption is still a thorn, think shady deals or court delays that mock justice. Some folks, especially Christians and Muslims, feel the Constitution’s secular vibe clashes with their faith, like when laws on marriage stir debates. Article 44’s protections get shaky when abuses go unchecked, far from the righteousness faith demands. It is tough, I tell you, how do you balance diverse beliefs in Gulu or Jinja with a law that is supposed to unite everyone? These gaps are not the Constitution’s fault alone; they are our challenge to live up to its call. Can we, Christians, Muslims, and others, push past these hurdles to make this sacred transformation real?

As Ugandans, we should have a call to action and forge this legacy; let’s make this Constitution more than ink on paper! It is a holy nudge to change how we roll, from Soroti’s markets to Entebbe’s shores. Article 1 says, “All power belongs to the people,” putting you in the driver’s seat to demand fairness and accountability. Think Matthew 5:16: “Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works and glorify your Father in heaven”, or Qur’an 13:11: “God does not change a people’s lot unless they change themselves.” Whether you’re Christian, Muslim, or ascribe elsewhere, this is your call to step up and push for transparent leaders, protect rights, and live out justice. The Constitution’s not just a rulebook; it is a spark for a righteous Uganda. Get loud about corruption, rally for fair courts, and build bridges across faiths. It is on us to turn this law into a legacy of love and unity. So, are you ready to act? Can we make this sacred transformation happen?

Conclusively, let us strive for a Legacy for Generations. As Uganda, we have come full circle! The 1995 Constitution is not just a legal playbook, but it is a sacred spark, lighting up a path for Christians, Muslims, and everyone else to live better, love deeper. It springs like John 13:34, saying “Love one another,” or Qur’an 49:13, celebrating our diverse tribes as one family. This is not about dusty laws; rather, it is about changing how we roll by pushing justice, building unity, from Lira to Kampala. Sure, we have got hiccups like corruption, debates, but the Constitution’s call is clear: be righteous, be one. It is our shot to turn faith into action, to make Uganda shine for generations. So, let us grab this covenant, live it loud, and build a legacy that makes our kids proud. Ready to make this sacred transformation real? Uganda’s waiting!

Attorney General of the 20th Nkumba University Law Society, President, Nkumba University Law Research Club, Papa Lawyers Fellowship, Chief Editor, 2nd Uganda Law Students Association Journal

Discussion about this post