Over time, Uganda’s music industry has witnessed growth in terms of sound and moral efficiency, yet its progress in legal matters remains sluggish.

Performing artists frequently enter into performance contracts, yet only a handful fully comprehend the profound implications of these agreements.

Dismissing the notion that legal affairs are a luxury reserved for wealthy artists, it is imperative for performing musicians to recognize that having a personal lawyer is no longer an extravagant choice.

Guidance on legal intricacies is essential to navigate the potential pitfalls concealed within deceptive musical contracts.

Understanding the nature and impact of contracts is vital, particularly within the legal framework governing contracts in Uganda.

While the court’s role in enforcing music contracts is not to make primary decisions, it ensures that the decision-maker adheres to the lawful requirements of contract law.

The legal landscape governing contracts in Uganda encompasses the Contracts Act, sale of goods and supply of services, with a specific focus on the Contract Act as the cornerstone.

It is crucial for artists to scrutinize the documents they routinely sign for performances, as a fundamental legal principle dictates that individuals are bound by written agreements they have signed, irrespective of whether they have fully comprehended the content. Waiting until later to assert, “it is not my deed,” can prove to be a costly and time-consuming endeavor.

Section 10 of the Uganda Contracts Act, No.7 of 2010 defines a contract as an agreement made upon free consent of parties with the capacity to contract for a lawful consideration and with a lawful object to be legally bound. Professor Trite also defines a contract as an agreement giving rise to obligations enforceable or recognized by law.

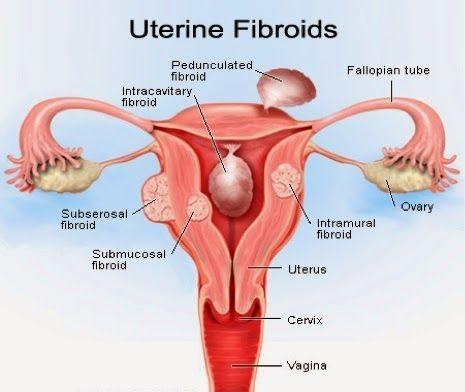

The law provides for the capacity (who should enter into contracts); however, many performing artists have no clue in regard to this. This follows that many make contracts in bars without having the compus mentis, and others allow minors (artists below 18 years) to enter into contracts which sometimes are not in the scope of necessity.

An example would be entering into a contract with Patrick Senyonjo alias ‘Fresh Kid’ (a young musician) to perform at a concert. This makes it a void contract ab initio because ‘Fresh Kid’ is not of an age that can contract under section 11 of the Uganda contracts Act, No.7 of 2010. However, this is subject to exceptions in law.

According to Contract Law by Catherine Elliott and Frances Quinn, For a contract to exist, usually one party must have made an offer, and the other must have accepted it.

Once acceptance takes effect, a contract will usually be binding on both parties, and the rules of offer and acceptance are typically used to pinpoint when a series of negotiations has passed that point, in order to decide whether the parties are obliged to fulfill their promises. Generally, no halfway house negotiations have crystallized into a binding contract or are not binding at all.

Breach of Performing Music Contracts in Uganda

It is a common occurrence for performing artists in Uganda to breach various contracts by declining to perform on agreed-upon platforms, resulting in significant damage to the equipment of promoters and other stakeholders.

The legal ramifications of such breaches are substantial. Breaching the terms of a contract can lead to the payment of damages as compensation to the aggrieved party, and these damages can be financially burdensome for an artist. The nature of damages may encompass the restitutio integrum aspect of the law.

Additionally, it’s crucial to be aware that failure to comply with such compensation orders can lead to imprisonment, a consequence that could tarnish the image of a performing artist and impact their fan base.

In related aspects of music contracts, there have been instances where governments and other authorities have arbitrarily canceled concerts and performances, adversely affecting the contractual commitments of music performers.

It’s important to note that shutting down a business without legal justification exposes a public entity to civil liability. This deviation from legal requirements can have serious consequences for both the performers and the authorities involved.

This was clearly propounded in the case of Siree v. Lake Turkana El Molo Lodges Ltd [2000] 2 EA 521, a District Officer directed the local police commander to close the Respondent tourist lodge and ensure that it remained closed until further notice, and he gave the reason for the closure as being that its proprietor had failed to pay various rents and fees and was not in possession of certain statutorily required licenses.

He recommended that the liquor license for the lodge not be renewed. The lodge, after that, commenced proceedings against the District Officer and the Attorney-General seeking damages on the grounds that the closure of the lodge was wrongful, arbitrary and unlawful.

Furthermore, the managing director of the lodge testified on its behalf, presenting a total of eleven licenses as evidence of compliance with relevant laws.

Despite this, the trial Judge held the Appellants responsible for wrongful closure without reasonable cause and ordered them to compensate the Respondent for damages incurred. In their appeal, the Appellants contended that the trial Judge had erred, arguing that the District Officer, being a government employee, had the authority to shut down the lodge. The court determined that licensing statutes governing lodges, including those applicable to the Respondent, such as the Trade Licensing, Hotels and Restaurants, Liquor Licensing, and Local Government Acts, delineated specific procedures for authorities to follow in cases of non-compliance.

Significantly, none of these statutes granted the District Officer the power to shut down an operation. Consequently, the District Officer’s actions exceeded his authority and constituted an abuse of power, rendering the Appellants liable for ultra vires acts, even in tribunals and courts of law.

In conclusion, it is prudent to affirm that the future of Uganda’s Music Performing contracts appears promising as long as performing artists are educated on the legal principles and requirements outlined in Uganda’s contract law.

Discussion about this post