International law (also known as Public International Law, or The Law of Nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognised as binding between states.

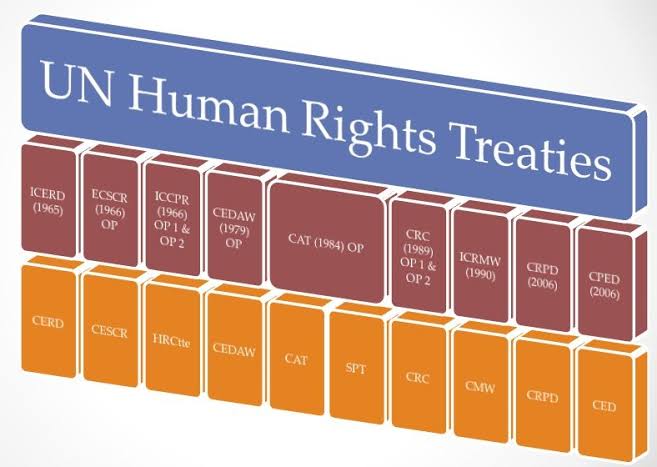

International human rights law can have a great impact on national systems. International law governs legal relations between states. The human rights values embodied in the U.N. Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights are all elements of customary international law that are rapidly establishing themselves as jus cogens.

Even though the sources of international law are not hierarchical, treaties enjoy some degree of supremacy, as they have sought to extend protection to all persons against governmental abuse.

It is important to note that states are primary actors in international law; each country is sovereign over its own territory, which means that the foreign government will determine how to investigate an attack, whether a crime has occurred according to its own law, and the manner in which any prosecution occurs in its own courts or tribunals.

International legal scholars have long recognized the importance of the relationship between international law and domestic legal systems.

Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice sets out the following sources of international law: a) international conventions, whether general or particular, establishing rules expressly recognized by the contesting states; b) international custom, as evidence of a general practice accepted as law; c) the general principles of law recognized by civilized nations; d) judicial decisions and the teachings of the most highly qualified publicists of the various nations as subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law.

The terms ratification, acceptance and approval all mean the same thing in international law, particularly when used following “signature subject to….” The State has agreed to become a party and is willing to undertake the legal rights and obligations contained in the treaty upon its entry into force.

When a state becomes a party to an international treaty, the state is bound to respect the treaty as a matter of international law and can be held accountable if it does not.

A state can express its consent to be bound by the treaty by ratification, signature or by an exchange of instruments constituting the treaty. This is governed by the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties of 1969. A decision to accede to a treaty is always made by the Government.

It is basically true that the international Human rights sets limits for states sovereignty, now the issue is to what extent international law also sets limits for national courts and public agencies in determining and dealing with human rights questions.

One of the main duties of government is to protect the rights of all persons. Access to courts and the right to an effective remedy are fundamental rights included in Article 8 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Articles 2 and 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

An international treaty seldom stipulates how the States should implement its provisions, leaving it to each State to decide how that obligation will be executed on the domestic level.

Legal systems do fall into groups or patterns with some similar features within each group. Among the main groups that you might encounter are: 1) common law; 2) civil law; 3) religious law; and 4) customary law.

It is also important to note that the relationship of international law to municipal law rests on two principal schools of law, i.e. Monists and Dualists. The dualists regard international law and municipal law as separate and municipal law can apply international law only when it has been incorporated into municipal law. Incorporation can result from an act of parliament or other political act, or given effect by the courts.

On the other hand, monists regard international law and municipal law as parts of a single legal system. According to this theory, municipal law is subservient to international law.

However in the case of Missouri v. Holland it is said that a treaty cannot be valid if it infringes the Constitution, that there are limits, therefore, to the treaty-making power, and that one

Most national legal systems now recognise custom as directly applicable, at least in principle, but generally consider it to be hierarchically inferior to domestic law.

The domestic enforceability of customary international law is manifest in the case of Filartiga v. Pena-Irala,was a landmark case in United States and international law, in this case Two issues were made clear by this case. Firstly, customary international law is a matter of universal jurisdiction, so that any national courts may hear extra-territorial claims brought under international law.

Secondly, domestic courts may discover international legal principles by consulting executive, legislative and judicial precedents, international agreements, the recorded expertise of jurists and commentators, and other similar sources.

In Uganda, courts have referred to various cases of human rights following the convention, for example, in the case of Susan Kigula & 416 ors V Attorney General, constitutional petition No.6 of 2003, in the judgment of court referred to the UN General Assembly Resolution 2857(xxvi) calling for the restriction of a number of offences for which capital punishment may be imposed.

Court also put into consideration the section 2 of the European Union Convention for the protection of Human rights and Fundamental freedoms in line with a right of life.

To become party to a treaty, a State must express, through a concrete act, its willingness to undertake the legal rights and obligations contained in the treaty – it must “consent to be bound” by the treaty.

In some countries, international (and at times regional) prima facie human rights law automatically becomes a part of national law. This case example can be on the treaty against death penalties. In other words, as soon as a state has ratified or acceded to an international agreement, that international law becomes national law. Under such systems treaties are considered to be self-executing.

In other countries, international human rights law does not automatically form part of the national law of the ratifying state. International law in these countries is not self-executing, that is, it does not have the force of law without the passage of additional national legislation.

In the absence of special agreements, a State will decide how to carry out its international obligations. For example, in the United States, the Federal government will decide whether an agreement is to be self-executing or should await implementation by legislation or appropriate executive or administrative action.

The following are the ways in which international Human rights treaties can impact the domestic legal systems.

National courts may look at international and regional human rights norms in deciding how to interpret and develop national law.

a case example can be the case of Andrew Mwenda & Anor V Attorney General No.12 of 2005 , where court put into consideration the international legal system against the offence of sedition to declare it ultra-vires and against human rights particularly freedom of speech and expression in the context.

The Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations of 1961 is another example and, most recently In Sweden, the UN Convention on the Jurisdictional Immunity of States and Their Property of 2004 was incorporated into Swedish law by means of a special Act passed in 2009.

Another example, the Kyoto Protocol is an international agreement on climate change. In this protocol, many countries have agreed to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in order to protect the environment.

Four main methods are generally available for the implementation of international human rights systems in domestic legal system:

Direct incorporation of rights recognised in the international instruments into a bill of rights in the national legal order;

Enactment of different legislative measures in the civil, criminal and administrative laws to give effect to the different rights recognised in human rights instruments;

Self-executing operation of international human rights instruments in the national legal order; and

Indirect incorporation as aids to interpret other law.

In the case of Pan-American World Airways Incorporated v SA Fire and Accident Insurance, in which he said

In this country, the conclusion of a treaty, convention or agreement by the South African government with any other government is an executive and not a legislative act.

As a general rule, the provisions of an international instrument so concluded, are not embodied in our law except by a legislative process … In the absence of any enactment giving its relevant provisions the force of law, it cannot affect the rights of the subject.

In the case Moosa & Others v Magistrate Ntlhakana & Others the Court took cognizance of the fact that ‘Lesotho has signed the African Union Convention on the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (sic) regarding the rights of citizens’ Makhasane was a trial for damages arising out of unlawful arrest and detention, as well as verbal and physical abuse In determining the amount of damages, the Court took into account the fact that the ‘African Charter protects a number of civil and political rights, including the right to dignity’, and held that such rights had been infringed by the police who unlawfully arrested and detained the complainant.

The Makhasane case illustrates the shift even more clearly in that the Constitution of Lesotho does not provide specifically for the right to dignity. Therefore, in finding that the plaintiffs’ right to dignity had been violated, the Court relied on Article 5 of the African Charter.

In the case of Basotho National Party & Another v Government of Lesotho and Others in which the applicant sought an order directing the government of Lesotho to ‘adopt such legislative and other measures necessary to give effect to the rights recognised in international conventions’, the Court dismissed the application and stated that ‘these Conventions cannot form part of our law until and unless they are incorporated into municipal law by legislative enactment’. The Court emphasised:

The Court cannot usurp the functions assigned to the executive and the legislature under the Constitution. It cannot even indirectly require the executive to introduce a particular legislation or the legislature to pass it or assume itself a supervisory function over the law-making activities of the executive and the legislature.

However, the impact of international legal systems has also been faced with challenges and negative consequences, as discussed below.

There is no rule of general international law that all treaties must have effect under domestic law. Many treaties have no domestic legal consequences and do not require implementation through the national legal systems of the States Parties. The freedom to choose some methods of implementation is also guaranteed in Article 2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which provides that: Where not already provided for by existing legislative or other measures, each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to take the necessary steps, in accordance with its constitutional processes and with the provisions of the present Covenant, to adopt such legislative or other measures as may be necessary to give effect to the rights recognized in the present Covenant.

In a nutshell, the various impacts of international Human rights Treaties on National Legal Systems have a great deal of importance, such as reducing torture, promoting fair trials, increasing religious freedom, promoting child health, reducing child labour or drafting the rights of women and children into national constitutions, this can be manifested in the bill of rights chapter for various Country constitutions.

Various cases and statutes have adopted international legal systems, such as the Uganda Prevention and Prohibition of Torture Act, 2012, which is a replica of the Convention against Torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations on 10th December, 1984 and ratified by the Republic of Uganda on 26th June, 1987.

Discussion about this post