Wampa Emmanuel

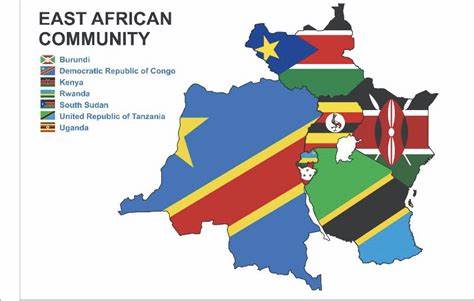

The East African Community (EAC) represents one of the most ambitious regional integration efforts on the African continent, aiming to bring together member states under a common legal, economic, and political framework. Comprising Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and South Sudan. The EAC seeks to create a unified market, establish a monetary union, and ultimately form a political federation. At the heart of this integration is the legal infrastructure that underpins cooperation and harmonization. However, the progress and efficacy of EAC law have been hindered by the persistent tensions between national sovereignty and regional commitments.

The legal foundation of the EAC is laid out in the Treaty for the Establishment of the East African Community, signed in 1999. This treaty outlines the objectives, principles, and institutional framework of the Community. It establishes organs such as the East African Court of Justice (EACJ), the Legislative Assembly, and the Secretariat to drive integration. The Treaty enshrines principles of good governance, rule of law, and human rights, aiming to foster deep political and legal unity among member states. Articles 5 and 6 of the Treaty elaborate on the objectives and fundamental principles of the Community, which include mutual trust, transparency, and peaceful settlement of disputes.

A central feature of the EAC legal regime is the principle of the supremacy of Community law over national laws in matters within the scope of the Treaty. This is a critical step towards harmonization, as it enables the uniform application of legal rules and policies across member states. However, in practice, this principle is inconsistently applied. National courts often assert jurisdictional primacy, and some states have been reluctant to implement EAC decisions that conflict with domestic law.⁴ The lack of a direct effect doctrine—unlike in the European Union—means that individuals and businesses often cannot directly invoke EAC law in national courts, reducing its enforceability and efficacy.

The East African Court of Justice has been a key player in shaping EAC law. Its jurisdiction includes the interpretation and application of the Treaty, as well as adjudicating disputes between member states, institutions, and individuals.⁶ Landmark cases such as Anyang’ Nyong’o v Attorney General of Kenya have reinforced the EACJ’s role in upholding the rule of law and democratic principles.⁷ Similarly, in Samuel Mukira Mohochi v Attorney General of Uganda, the EACJ held that Uganda’s refusal to allow a Kenyan national entry without explanation violated the Treaty’s provisions on free movement and non-discrimination.⁸ In Independent Medical Legal Unit v Attorney General of Kenya, the Court ruled against police brutality and enforced the Community’s commitment to human rights. However, the court’s limited jurisdiction—particularly its inability to hear human rights cases under the Treaty—has been a significant obstacle. Proposals to expand its mandate have faced political resistance from member states wary of ceding judicial authority.

Legal harmonisation has seen success in areas such as customs law and trade facilitation. The EAC Customs Union Protocol, established under Article 75 of the Treaty and operationalised in 2005, is the first pillar of EAC integration. It provides for the elimination of internal tariffs, the establishment of a common external tariff (CET), and harmonisation of customs procedures.¹¹ This has enhanced intra-regional trade and simplified border procedures. Cases such as British American Tobacco (BAT) Uganda Ltd v Uganda Revenue Authority have illustrated the application of the Protocol where disputes concerning tariff classification and customs valuation have arisen.¹²

The Common Market Protocol, adopted in 2009 and entered into force in 2010, is founded on Article 76 of the Treaty. It guarantees the free movement of goods, persons, labor, services, and capital across partner states. It also provides for the right of establishment and residence. In Modern Holdings (EA) Ltd v Kenya Ports Authority, the EACJ dealt with issues concerning freedom of establishment and equal treatment of investors, thereby reinforcing the principles of the Common Market Protocol.

Despite these advances, implementation remains uneven. Non-tariff barriers such as administrative delays, protectionist measures, and differing standards continue to hamper the smooth operation of the customs union and common market. The EAC Secretariat’s annual reports continue to highlight member states’ non-compliance with agreed timelines and procedures. Moreover, legal reforms are often top-down, with limited participation from civil society or national legislatures, weakening their democratic legitimacy.

One of the most contentious issues is the balance between integration and national sovereignty. While the EAC Treaty calls for political federation, member states remain protective of their sovereignty. This manifests in selective implementation of Community decisions, delays in ratifying protocols, and resistance to judicial scrutiny. ¹⁶ the divergent political systems and legal traditions of member states further complicate harmonization. For instance, while Kenya and Uganda have relatively independent judiciaries, other states have been criticized for political interference in legal processes. ¹⁷ Such disparities affect mutual trust and the uniform application of EAC law.

Another legal challenge lies in the enforcement mechanisms of the EAC. Unlike the European Union, the EAC lacks robust mechanisms to sanction non-compliance. The EACJ can issue declaratory judgments, but enforcement depends on the political will of national governments. The absence of a supranational enforcement body means that breaches of EAC law often go unpunished. This legal vacuum undermines the authority of EAC law and weakens the integration process. Cases like Henry Kyarimpa v Attorney General of Uganda demonstrate the ineffectiveness of enforcement when states choose not to comply with rulings.

Despite these challenges, the EAC legal framework has made notable strides in fostering cooperation and providing legal certainty in specific sectors. Regional institutions such as the East African Legislative Assembly (EALA) have contributed to the development of Community law, though their capacity is often limited by political constraints and resource shortages. ²⁰ The proposed Monetary Union and common currency will require further legal harmonization, particularly in financial regulation, fiscal policy, and central banking. Such integration necessitates not only legal but also political convergence, which remains a work in progress.

In conclusion, the law of the East African Community presents a complex picture of aspiration and limitation. While the EAC has established a legal framework aimed at deep integration, practical implementation is constrained by sovereignty concerns, legal fragmentation, and weak enforcement mechanisms. To realize its full potential, the EAC must strengthen the authority of its legal institutions, enhance the direct applicability of Community law, and foster political commitment to regionalism. Only then can the law become a true vehicle for unity, development, and justice in East Africa.

BY: Wampa Emmanuel (Secretary, Research Club, School of Law)

Nkumba University

0779816870

Ewampa7@gmail.com

Discussion about this post