As Uganda marks the 30th anniversary of its 1995 Constitution on October 8, 2025, the document stands as a pivotal milestone in the nation’s turbulent history. Promulgated after years of political instability, it promised a new era of democracy, human rights, and governance. Yet, three decades later, reflections from legal experts, civil society, and scholars reveal a mixed legacy: significant achievements overshadowed by persistent challenges, including manipulations that have entrenched executive power. This article explores the background of the Constitution’s creation, its key gains, and ongoing challenges, drawing on landmark case law, insights from renowned scholars like Dr. Busingye Kabumba, and perspectives from President Yoweri Museveni’s autobiography, Sowing the Mustard Seed.

Uganda’s post-independence history was marred by constitutional upheavals that set the stage for the 1995 document. The 1962 Independence Constitution established a federal system but was suspended in 1966 by Prime Minister Milton Obote, who introduced a republican constitution vesting immense powers in the presidency. This was followed by the 1967 “Pigeonhole Constitution,” further centralizing authority. Idi Amin’s 1971 coup abolished these frameworks, ruling by decree until his ouster in 1979. Subsequent regimes under Yusuf Lule, Godfrey Binaisa, and Obote’s second term (1980–1985) perpetuated instability, with widespread human rights abuses and military dominance.

The National Resistance Movement (NRM), led by Yoweri Museveni, seized power in 1986 after a five-year bush war. Museveni, in his 1997 autobiography Sowing the Mustard Seed: The Struggle for Freedom and Democracy in Uganda, frames this period as planting the “mustard seed” of democracy, a metaphor for gradual democratic growth in a fractured society. He argues that for the seed to flourish, the “soil” (Uganda’s political landscape) must be prepared, critiquing hasty multipartyism in favor of a “no-party” movement system to foster unity. Ironically, Museveni lambasts African leaders who overstay in power, stating in the book that such rulers hinder progress, a view that contrasts with his own 39-year tenure.

To legitimize his rule, Museveni established the Uganda Constitutional Commission (UCC) in 1988, chaired by Justice Benjamin Odoki, to draft a new constitution through public consultations. Over 25,000 submissions were collected, reflecting diverse views on governance, human rights, and federalism. A Constituent Assembly (CA), elected in 1994 with 284 delegates (mostly NRM-aligned), debated the draft from March 1994 to September 1995. Challenges included NRM influence, factionalism, and debates over multipartyism, which was initially suspended under Article 269. The CA adopted the Constitution on September 22, 1995, and it was promulgated on October 8, establishing a quasi-parliamentary system with an executive president, legislature, and judiciary. Odoki later highlighted unique “home-grown” elements, such as the emphasis on unity and social justice, influenced by Uganda’s history of division.

Dr. Busingye Kabumba, a prominent constitutional scholar, critiques this process in his writings, arguing it was undemocratic. In a chapter on the Constitution as a “tool for dictatorship,” he notes Museveni’s unilateral appointments to the UCC and daily interventions in CA debates, creating a “false majority” to entrench NRM interests.

Uganda’s post-independence history was marred by constitutional upheavals that set the stage for the 1995 document. The 1962 Independence Constitution established a federal system but was suspended in 1966 by Prime Minister Milton Obote, who introduced a republican constitution vesting immense powers in the presidency. The “Pigeonhole Constitution,” further centralizing authority. Idi Amin’s 1971 coup abolished these frameworks, ruling by decree until his ouster in 1979. Subsequent regimes under Yusuf Lule, Godfrey Binaisa, and Obote’s second term (1980–1985) perpetuated instability, with widespread human rights abuses and military dominance.

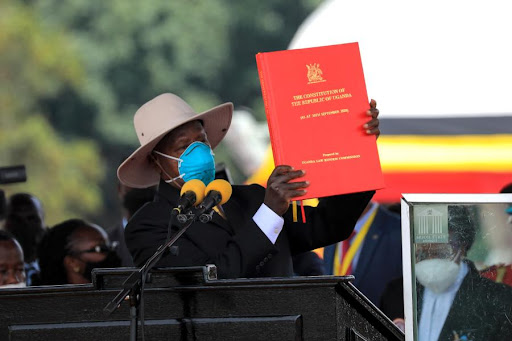

The 1995 Ugandan Constitution book cover, symbolizing the foundation of human rights protections. It enshrines a robust Bill of Rights (Chapter Four), protecting freedoms of expression, assembly, and equality, while prohibiting torture and discrimination. This framework has enabled the ratification of international treaties and conventions on culture and human rights, facilitating capacity building and cooperation in these areas. For instance, it has supported advancements in environmental management and social justice, aligning with global standards.

Decentralization under Chapter Eleven empowered local governments, initially with 35 districts, promoting grassroots democracy and service delivery. This has led to improved citizen participation, better local governance, and the ability to bring services closer to the people, such as in health and education. Environmental and natural resource management has been devolved to districts since 1996, enhancing local accountability. While it has sometimes increased local conflicts, it has overall reduced national-level tensions by distributing power.

The document also advanced gender equality through affirmative action, such as reserved parliamentary seats for women, ensuring gender balance and fair representation. This has led to progress in women’s political leadership, with women occupying significant positions and contributing to policies on education and climate action. The Constitution prohibits gender discrimination, sets the marriage age at 18, and provides equal rights in marriage, opposing practices that violate women’s dignity. The establishment of the Equal Opportunities Commission has further worked to eliminate discrimination in employment and other areas.

Economically and socially, it facilitated stability, enabling growth and poverty reduction in the early years. Museveni’s Mustard Seed credits this to the NRM’s focus on unity, arguing the Constitution provided a framework for “freedom and democracy” by rejecting sectarianism. Post-1995, Uganda experienced steady GDP growth, as evidenced by economic charts showing recovery and expansion. (Note: Refer to economic growth charts for visual representation.)

Landmark cases have upheld these gains: In Uganda Law Society & 12 Others v Attorney General (Constitutional Petition 32 of 2020) [2024] UGCC 2 (13 February 2024), the Constitutional Court affirmed anti-discrimination protections under Article 21. Similarly, Foundation for Human Rights Initiative and Others v Attorney General of Uganda (Constitutional Petition No. 3 of 2015) [2025] UGCC 10 (11 August 2025) struck down an unconstitutional law, demonstrating judicial enforcement of rights. Other notable rulings include Attorney General v. Susan Kigula and 417 Others, No. 03 of 2006, Uganda: Supreme Court, 21 January 2009, where the Supreme Court declared mandatory death sentences unconstitutional, advancing the right to life. In Perez Mwase and 2 Others v Buyende District Local Government and Attorney General, H.C.C.S No. 135 of 2017, the court emphasized the right to human dignity under Article 24. Additionally, cases like CEHURD v. Attorney General Constitutional Petition No. 16 of 2011 have addressed maternal health rights, interpreting the right to health broadly.

Civil society reflections at the 30-year mark praise the Constitution for interrupting cycles of violence and establishing checks and balances, with the judiciary occasionally delivering bold rulings on human rights. A recent compendium of 24 landmark cases highlights its role in public interest litigation and constitutionalism compiled by The Fedelis Leadership Institute.

However, the Constitution’s promise has been undermined by profound challenges, including frequent amendments that facilitate prolonged rule, institutional erosion, and a disconnect between its ideals and reality. Dr. Kabumba, in his 2012 article “The Illusion of the Ugandan Constitution,” describes it as an “illusory law,” where Article 1’s claim that “all power belongs to the people” is a façade, real power resides with the President and the military. He cites examples like the 2007 “Black Mamba” paramilitary siege of the High Court to block bail for opposition figures, and Museveni’s dismissal of judges as mere handlers of “chicken and goat theft” cases. In a 2024 book launch, Kabumba called it a “book of lies,” arguing its high-sounding provisions mask executive dominance. Expanding on this, Kabumba critiques the constitution-making process as flawed and imposed by the NRM, with the preamble’s “We the people” being a lie, as the Constituent Assembly elections banned political party campaigning, and the commission was NRM-dominated. He further argues that Article 2, declaring the Constitution as supreme law, is contradicted by the lack of independent institutions, and Article 22’s protection of the right to life has failed to prevent extra-judicial killings, such as the 2016 Kasese massacre and the 2020 protests where 54 people were killed, leading to societal mob justice.

Amendments have been central to these issues, with over 120 changes in the first 19 years alone, often through non-participatory processes lacking citizen input. The 2005 removal of presidential term limits under Article 105, allegedly involving bribery of parliamentarians, and the 2017 elimination of age limits under Article 102, allowed Museveni indefinite rule. These were challenged in cases like the 2018 consolidated petitions, where the Constitutional Court upheld the changes despite public outcry and violent parliamentary sessions. Election petitions, such as Kizza Besigye v. Yoweri Museveni (2001 and 2006) and Amama Mbabazi v. Museveni (2016), acknowledged irregularities but upheld results, highlighting judicial ambiguity. The 2021 Robert Kyagulanyi (Bobi Wine) v. Museveni petition followed suit, with courts noting fraud but declining to annul the election.

Scholars like Kabumba argue these amendments exemplify “constitutional autocracy,” where the document is manipulated for patronage and coercion. Framers themselves express regrets: Chief Justice Alfonse Owiny Dollo lamented not entrenching term and age limits with referendum requirements, calling it a “mistake” that allowed easy alterations. Former Prime Minister Kintu Musoke regretted the unforeseen rise of family rule and settling for a unitary system over federalism for regions like Buganda. Political veteran Peter Walubiri criticized the Constitution as built on “quicksand” to entrench Museveni, with a partisan Assembly and ignored Bill of Rights, leading to detentions beyond 48 hours and institutionalized corruption.

Further, entrenched provisions under Article 5(2), meant to protect core democratic elements like separation of powers and fundamental rights, have been non-fulfilled. For example, presidential immunity under Articles 98(4) and (5) was upheld in Tumukunde v Attorney General & Anor (Constitutional Petition No. 6 of 2005) [2005] UGCC 1 (26 August 2005), placing the president above the law, and in Prof Gilbert Balibaseka Bukenya v Attorney General (Constitutional Petition No. 30 of 2011) [2011] UGCC 9 (10 August 2011), limiting accountability. Freedoms of assembly were undermined despite Muwanga Kivumbi v Attorney General (Constitutional Petition No. 9 of 2005) [2008] UGCC 34 (27 May 2008) striking down prohibitive laws; the subsequent Public Order Management Act 2013 restored restrictions. Oversight failures, like vacancies in the Inspector General of Government positions since 1995, were highlighted in Hon Sam Kuteesa & 2 Ors v Attorney General (Constitutional Reference No. 54 of 2011) [2012] UGCC 2 (4 April 2012). Decentralization has ballooned to over 140 districts, fostering dependency and corruption rather than empowerment.

These challenges reflect a “constitutionalism deficit,” where the document enables rule by law rather than the rule of law, perpetuating elite interests and ignoring issues like youth unemployment and ethnic marginalization. Museveni’s book, while advocating democracy, has been critiqued as a scheme to justify personal rule, with his rereading of Frantz Fanon’s violence theory enabling military-backed governance. Civil society laments “capture by fear,” with parliament as a “lapdog” and widening inequality betraying the Constitution’s ideals. Calls for a citizen-led constitutional audit and referendum underscore the need to reclaim its spirit and address these entrenched flaws.

Conclusively, at 30, Uganda’s 1995 Constitution stands at a crossroads, embodying both a beacon of hope and a contested instrument. Its achievements in establishing a framework for human rights, decentralization, and gender equality are overshadowed by persistent challenges, including amendments that entrench executive power, institutional erosion, and a growing disconnect between its lofty ideals and lived realities. To fulfill its promise, a robust, citizen-led constitutional audit is essential, one that re-evaluates entrenched provisions, strengthens judicial independence, and ensures genuine separation of powers. Civil society and scholars advocate for a referendum to restore democratic integrity, addressing issues like youth unemployment, ethnic marginalization, and corruption that undermine the Constitution’s vision.

Dr. Busingye Kabumba captures this urgency in his profound reflection on constitutionalism: “A constitution is only as strong as the will of the people to defend it; without their vigilance, it becomes a mere parchment, a tool for the powerful to mask their dominion.” Only through collective action and renewed commitment can Uganda cultivate the fertile soil rooted in true democratic accountability and citizen engagement needed to let the mustard seed of democracy, as Museveni envisioned, truly flourish in the next 30 years.

Discussion about this post